Describe the structure of this anime, and you’ll get a shounen. Add the genders of the characters, and it’ll read as if this anime tries to deconstruct both Shoujo and Shounen for some grand statement about anime, sexuality and the target audience. Watch it, and it’s just a simple story about collecting plot coupons in the shapes of handsome guys which all happen to be engaging characters. It’s odd how Yona opted for doing a simple adventure story when it could do so much more.

It’s not bad, just bizarre. Most anime – or stories in general – that aim for a simple, exciting adventures have low aspirations. They aim for a bit of fun, some wacky designs and battles, a few dramatic mission statements and a big explosion to signal the climax. Yona has all the ingredients to uplift this formula to something serious, yet it’s content in basic storytelling. At least it has a good reason. As an example of adventure stories, Yona is fantastic.

The first thing a storyteller must decide is what’s the meaning of his adventure. This meaning doesn’t have to be explored with all its philosophical layers and references to dead white European males. Rather, this meaning will serve as an emotional core, to make us care about what’s going on. We always care about things because they mean something, anything.

Yona starts with emotional hooks and never lets them go. A common mistake is turning your adventure into a set of obstacles to overcome using skills and badassery. Yona, instead, has a running theme connecting all these stages. What’s dominating is a specific type of coming of age. It’s not just about learning about the world outside, but realizing how different the bubble you were in is to the world.

What makes characters interesting and meaningful is what they do with their circumstances. Yona’s bubble doesn’t just burst. Rather, she doesn’t give up on her bubble but tries to reform it. In every place she goes to, she uses the lessons she grew up on – love, comfort, and softness – and bestows it upon the people. Her battle against the trafficking of women isn’t plain morality. Yona aims for a specific type of world, some kind of replica of what she used to live. Notice her treatment of the dragons. She never demands that they’ll join her moral crusade. She reacts in the same way her father did, she hopes they’ll join them of her own will. Her gang is designed like her father’s world, where everyone is nice to each other.

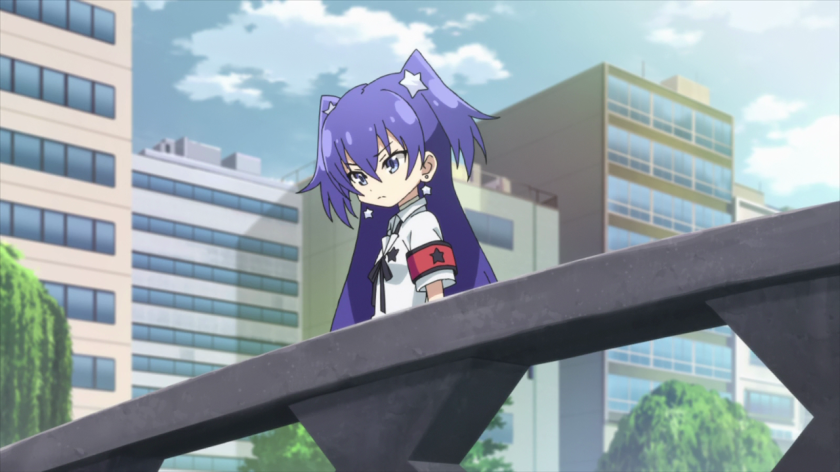

As a female character, Yona is fascinating. On the surface, she’s a weak female character who needs her guys, weapons, and a shorter hair for validation. That’s because we’re so used to aggressive personalities. Even if our women aren’t warriors, we expect strong characters to shout and care nothing at all about others.

Yona may be feminine, but it is hardly a weakness. She has a worldview that guides her, that is uniquely hers. The actions are never convenient and her moral system isn’t a simple case of doing good. Beyond that, everyone actually relies on her. The source of meaning isn’t just a way of moving the plot. The dragons don’t join smoothly, and each views their situation differently. Nevertheless, Yona is the ultimate guide of the gang. The meaning of the journey, of remaking the world as a softer, more comfortable place to live comes from her.

Although she rarely takes active, aggressive action she always remains dominant. That’s because every conflict is an examination of her personality, and she changes. Everyone else just helps her with the technical details of getting food and scouting.

The anime also treats its antagonist well. Soo-won is a character of contrasts. His presentation is always a flip of what we before. It goes beyond the beginning, where he’s a smiling angel who turns out to be murderous. In two episodes, he’s the main character. We see how he runs the kingdom, what his views are of how it should be. It’s a shame the series is so short and doesn’t give him enough screen time. He’s a cold, calculated person who’s a fantastic actor. He also, when choosing a purpose, pursues it aggressively.

An aggressive personality doesn’t necessarily translate to a cruel reign, but an efficient one. In a few instances, the anime is an excellent exploration of a benevolent monarchy. Although Soo-Won is cold, his aggressive pursuit brings him to a lot of victories. He manages to lift up a situation that King Il couldn’t, and without aggression he couldn’t do that. It’s a shame he has little screen time. The creators use the screen time to display both sides, but they never clarify the connection between them.

Each arc stands on its own, carry its own meanings, main characters and tones. The anime borders on experimental, with one arc flirting heavily with horror. The result is that despite having a structure of plot coupons, it never feels this way. Yona needs to collect all dragons to cash them in for End of Plot, but each tale of getting the coupon stands for itself. The stories are so different. One is about a comically religious village. Another is about an underground village living in constant fear. Another is about overthrowing the asshole ruler. Separate these stories from the big picture, and they stand on their own. A formulaic structure doesn’t matter so long as the parts are good, and this anime is a clear proof of this.

That’s why although its ending is one of the worst in the style of ‘no ending’, it’s still great. Many complain about anime that don’t really end, but often they do conclude their small arc. Yona is one of the few that builds up to a big conflict and never gets to it. It doesn’t even use its final arc to conclude all the ideas that happened before. The anime doesn’t set itself up as an episode in a gigantic story – like, say, Attack on Titan – but a straightforward adventure where we expect the hero and the villain to meet at the end for some milk, cookies, philosophical discussions and an exchange of blows. It ends by collecting all the coupons and never cashing them in. Since everything that happened before is good enough, it doesn’t ruin the anime but it’s still disappointing.

The art style is delightlyfully shoujo. The eyes are quite big. Yona is feminine, with a red hair that’s not just red, but sore red. It’s the kind of red that you don’t wear to your workplace because it’s too attention-grabbing. The guys are also all handsome. While the designs are appealing, few are distinct. Yona is beautiful, but that’s expected from a shoujo anime that doesn’t think feminine is an insult. As for the other characters, only Soo-Won has an interesting design. His soft side is expressed in his long, bright hair and warm expression that has a long, rather than wide smile. Everyone else fits their characters, but Hak’s rugged look is typical dark short hair. Yun is another honorable mention. As an attempt to make a pretty boy, it’s excellent. We never see much of this handsome male look. We see male characters who are handsome, but not those whose looks is a major selling point.

Yona is a straightforward adventure anime. What it aims to do isn’t special, but what makes it special is how well it understands the adventure story. It manages to overcome a non-existent ending, and you can only do that by having separate arcs which still gel together, by having characters that breathe life to these arcs. Occasionally, it shuffles the pieces around but it’s more for entertainment effect rather than subversion. Still, if you want to experience pure storytelling, this is it.

3.5 dragons out of 5

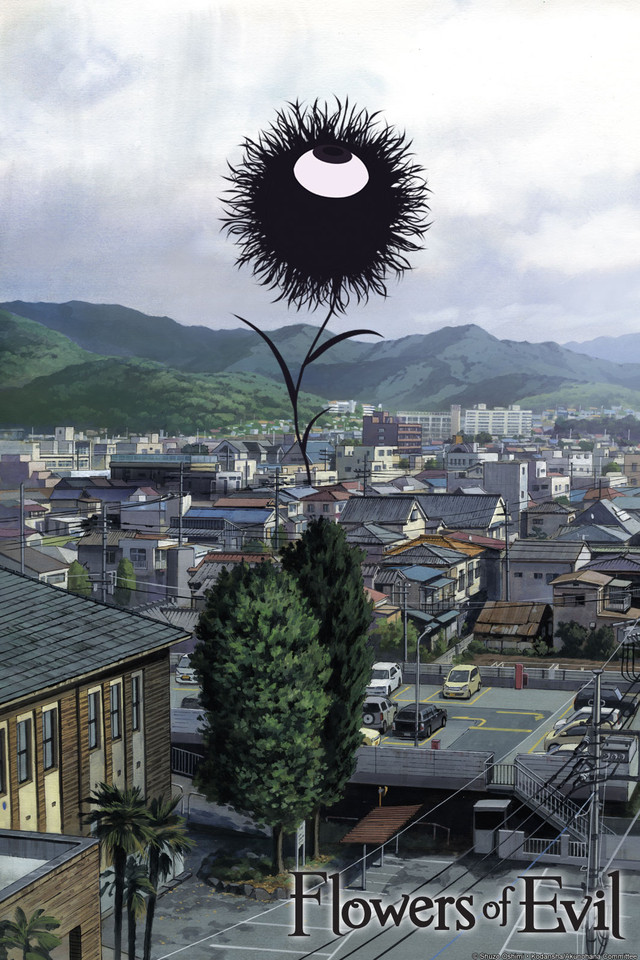

Just a while ago, I read a Young Adult novel that seems to be the positive mirror of this. It was Jennifer Brown’s Hate List. Both novels deal with a tragedy, specifically a girl losing a boy to death and how it affects their lives. The relationship was big. Both happen to be outcasts in a Nowheresville. Relationships with the family is rocky and there is a sexually-active, supposedly hot chick that’s evil involved.

Just a while ago, I read a Young Adult novel that seems to be the positive mirror of this. It was Jennifer Brown’s Hate List. Both novels deal with a tragedy, specifically a girl losing a boy to death and how it affects their lives. The relationship was big. Both happen to be outcasts in a Nowheresville. Relationships with the family is rocky and there is a sexually-active, supposedly hot chick that’s evil involved.

Note: this series has been dropped at episode 14

Note: this series has been dropped at episode 14