Often you’ll hear how being unique isn’t enough to make a good anime. That’s not entirely true, since being unique is overall a good trait. Why would you want to sit in front of a screen, watching the same thing over and over? What these people do get right is that mere uniqueness isn’t enough. Although in the end, all great works of art are unique and highly original, not all original works are great works. That’s because true greatness which comes from true uniqueness isn’t just a unique art style or a cool storytelling method, but a thematic depth.

All the problems with this anime are in this sector. It’s eccentric and utterly bizarre. Better anime don’t break their conventions like this, but in the end it’s all just quirks and a unique style that don’t reach any profound conclusion. As an aesthetic experience, it’s awesome with how wacky it is. As for its narrative, it’s just there.

The narrative is fairly empty and the symbols, while cool, don’t mean anything. Having a psychiatrist and people with psychological disorders isn’t an automatic ticket for actual character psychology. The anime mistakes exaggeration for madness, like a 16-year-old kid who thinks a Facebook cover photo with blood shows how ‘crazy’ they are.

The anime deals with the old notion of ‘crazy’, something that I think the mental health institutions abandoned even before Thomas Szasz took an axe to their heads. Here characters don’t struggle daily with a disorder. The problem isn’t present in every fabric of their existence but, rather, explodes out of nowhere. Most of these characters lead normal lives until something triggers them.

Now, it’s true that a lot of mentally ill people function day-to-day, interact with people and buy eggplants without causing a massacre. Notice how their normality is only something we experience. They don’t. Someone who is suicidal (A major problem that the series oddly avoids) is always suicidal. Some days it hurts less, some days it hurts more. However, the normality is only an external thing.

Inside, everything pushes him towards death. For the depressed person, every thing demands extra effort and the question of ‘why go on?’ is always present. That’s why mental illness is such a problematic thing and a lot of philosophers had to step in to redefine it. Mental illness is not a wound, it’s not a specific area of the body we can target and diagnose and seperate. Mental illness is an integral part of being. Depression isn’t a distortion of reality but a part of someone’s personal reality.

The characters here aren’t even reduced to their mental illness. They’re reduced to their onsets. Although we see them do ordinary stuff like jobs and family, we rarely get insight into how they exist with this. It’s all just build-up until the dude panics over not being sure if the stove is on. This prevents the show from having any serious psychology. In order for it to be truly psychological, it needs to present these people as whole human beings and it needs to show how the illness relates to the whole.

In truth, these aren’t really characters. Their disorder defines them more than anything. Most of the differences between them comes from that. The show belongs to the tradition of a main character who’s a vessel for other stories. In general these type of anime have a cool style and an empty narrative. It’s not just because there is no major conclusion – although it tries for something sappy like how we need to listen to others. Their problems are also very illness-orientated.

If mental illness was so exaggerated and obvious, we would’ve had an easier time dealing with it. We don’t. The problems these characters face tend to be only their illness. How it relates to other problems is unclear. Sure, it disrupts their day-to-day life but that’s not enough. How does it affect sexuality, social interactions, worldviews? The series loves to portray extras as cardboard, but in truth no one is cardboard for people. Our ilness and these passerbys are part of our lives. The anime treats mental problems like an obvious wound.

It doesn’t help that most of the stories involve OCD. I’m sure it’s a common disorder, but where’s schizophrenia, depression, bipolar? Perhaps because OCD is far easier to exaggerate. It has onsets, things that are easy to transmit visually. Depression is harder since depression is everywhere, showing itself in every action and relates to a person’s inner life. You have to show a worldview in order to portray depression. That’s why its status as an illness is such a problematic issue. Eventually, all these people with OCD blur into one another. The only thing that changes is how it works.

When a different illness comes, they fail to show its psychology. A person’s narcissism ends up being monotonous. The big problem isn’t narcissism, but a dude who can’t stop smiling. The whole agony of living in the past, in glory days that are never to return and trying desperately to re-create them isn’t there. Rather, it’s just a person repeating his shtick over and over. It’s an excellent example of how they take a serious issue and reduce it to a single symbol, stripping it of any depth.

The surrealistic, bizarre art and storytelling also leads to an air of self-satisfaction. It’s not as bad as it looks from the outside, but it’s there. Nothing is particularly funny about these jokes, since they don’t point to any absurdity and hardly a taboo. So the psychiatrist gets off on vitamin shots. That’s kind of odd and amusing, but not out of place. Early on the anime establishes how wacky it is with these colors, so this is fairly ordinary. Irabu is also not really funny, just quirky and high-pitched. There’s also a sexy nurse who thankfully has little screen time. Her role is mainly to inform the viewer that the makers are totally fine with ultra-sexy yet placid women, some pathetic symbol of ‘sexual strength’. I don’t know. Nothing about her is interesting, including breaking into live-action. Overall, the series sets itself up as weird, but can’t ever up the weirdness.

It’s not all bad though. In fact, in its format, the anime is quite excellent. It’s the old format of a single main character whose a narrative device to show the lives of various characters, like Kino’s Journey or Mushishi and it does it so much better.

First off, merely dealing with mental disorders – an integral part of the experience of being – gives these stories a more emotional, personal angle. Already here it lifts itself up above the aforementioned anime. Unlike them, there is some sort of humanity here. It’s exaggerated, caricature-esque and shallow but it exists. The main driving symbol has a far more personal nature so the stories are by their nature more emotionally engrossing. The distance that harmed Mushishi is mostly absent.

There’s also concern and empathy for these characters. For all its exaggeration, the series has some awareness that underneath it all there should be humanity. The tone is not mocking, something that the aesthetics and the ultrasexy nurse hint at. Rather, it’s empathetic towards these little lost humans and their madness. Episodes don’t end with a complete return to normality, but with a way to cope with the madness.

It’s this vibe and demeanor that prevents the anime from being only an exercise in aesthetics. There is a clear meaning underneath some of these symbols, like how cardboard-like people merely means these aren’t important characters. The mental conditions are caricatures, but at least they make sense – extreme worry is a problem. Even if the series isolates these parts, it does fit with the style. In a way, the series never pretends to actually be psychological. From the start it’s concerned more with flash than substance, but it has just enough substance and humanity to prevent it from being vapid.

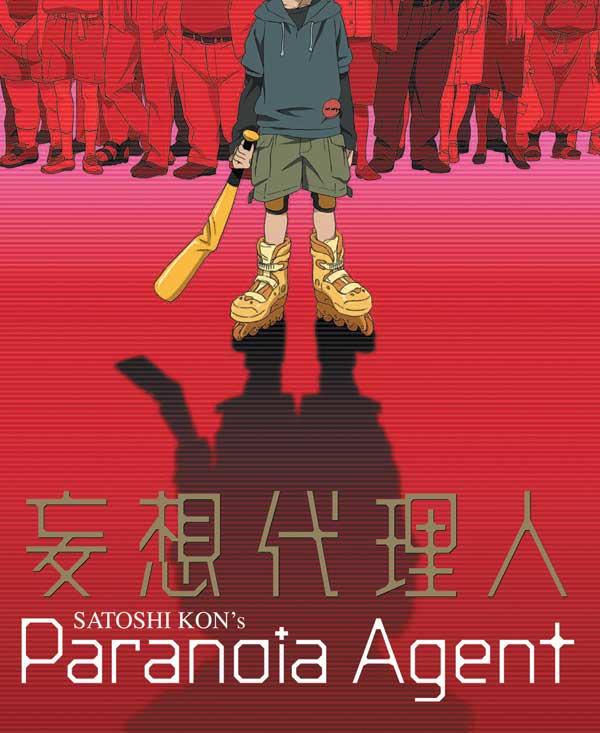

As for its aesthetics though, they’re fantastic. It’s true there isn’t an anime quite like this one. You might compare its surreal style to Tatami Galaxy, but that one had an overbearing, total aesthetic. Here they take a realistic art style and utterly distort it, creating a weird clash of realism and cartoon. The storytelling is knowingly expressive, so much so that sometimes things don’t have meaning. There are polka dots everywhere, but then again why not? It’s self-awareness which doesn’t try to be clever. Knowing that none of it is real, they let themselves go with wacky, memorable images. It’s a style weird enough to hold on for 12 episodes even if there isn’t much variety among them.

Utterly bizarre and original, yet its lack of depth prevent it from being one of the greats. It had the premise and the aesthetic boldness, but it’s also satisfied in just being fun. Often we talk about how ‘just fun’ shows need to be unoriginal, yet this anime demonstrates you can have fun without aiming too high. Set expectations about how mind-blowing this is, and you’ll be disappointed. This is just another in the long line of episodic anime with a wide cast, but its one-of-a-kind style breathes life to the format.

3 crazies out of 5