Along with fat men, philosophy and Skrillex, Christianity is now one of the definitive expressions of the ‘uncool’. Call yourself a Christian, and you’re no fun, too moral, antisexual and you must be preachy (Unlike all those atheists writing a lot of books). We’ve heard how Christians dominate the media. For example, Slayer’s anti-religious music sells a lot less than Thousand Foot Krutch’s God-praising anthems.

Actually, that doesn’t really happen. The problem with putting yourself all the time in the position of the rebel and iconolast, you can’t realize when you’ve already won and create a new class of victims. Now, I’m not saying Christians are an oppressed group. Considering their size and the millions sects, it’s an absurd statement to make because there’s little way of knowing if they are. Nevertheless, Christianity is under attack.

Firs it begun in the Academia with Kierkagaard and eventually Existensliam. All around in culture you found opposition to Christianity, whether these are stories of how badly they treated Africans or loud rock songs against God. Reading this book in this time and age is so bizarre. A defense of Islam or even Judaism we can tolerate – these are the Other culture, so we refrain from judging. How can someone praise Christianity, especially Catholicism? Aren’t they all privileged?

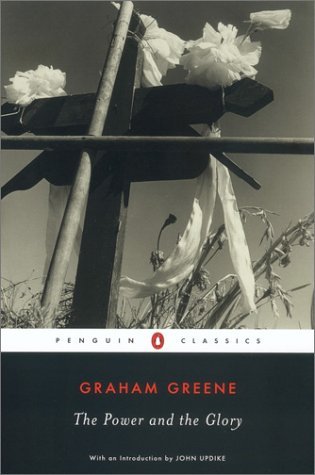

It’s undoubtedly a Christian novel that not only features a priest of a lead character, but deals with themes in the Catholic perspective. While I’m not well-versed in Catholicism and I’m sure theologians can find many a hidden meaning, the familiar themes raise their heads. Fear, trembling, sin, guilt, forgiveness are the dominating themes here along with the pessimistic view of the religion.

Catholicism is a fairly pessimistic worldview. Although they object to suicide, their view of the world is negative. The world is a bad, harsh place full of suffering. Greene’s Mexico isn’t just a critique of how Catholics were treated, but how the world is for all of us. This Mexico is hostile to everyone. The Whisky Priest is as much of a plot device as he is a character, showing us the various lives of others.

Each of them suffer because of the world they’re in. If the priests are traitors, they are only traitors because they try to give meaning to the suffering in this world. In this world people, in a way, forsake meaning. The boy refuses to listen to his mom reading books, and so does not connect to the family. It is a land not concerned with meaning. When the police takes hostages and shoots them until they give up the priest, it’s a future critique of Charles Taylor’s ‘instrumental reason’, when we think only of how to solve a problem instead of how to fix it.

Yet it’s not a self-righteous novel at all. The idea of a ‘whisky priest’ is one that preaches virtue but cannot practice it. That’s because integral to Catholicism isn’t just sinning, but forgiveness. There is this struggle between the weight of sin which is the source of evil and forgiveness, which is supposed to be the source of good. Greene isn’t interested in preaching his religion but exploring and expressing this struggle.

That’s why, in the end, this novel isn’t exactly religious. It merely deals with themes which Catholics consider more important than, perhaps, making a lot of money or coming up with a new viral video. This focus on sin and forgiveness births a synthesis. Greene is deeply interested in human beings as they are.

Like the best realists, even when his characters can be dry he draws them sympathetic in their flaws. For the whole novel we’re encouraged to hate the police. Then at the end Greene gives them more than a voice, he gives them the ability to forgive and empathize. He recognizes ‘sin’ depends on who you ask, and that for the police being a Catholic priest is a sin. Greene gives the antagonist his moment of spotlight, pushes his humanity out and show us he’s capable of forgiveness. There’s still a bit of demonization there, although Greene tries hard not to do it. The uselessness of religion is talked about and demonstrated throughout the novel. When the bad guy goes off on his rant, there’s still a bit of narrow-mindedness there.

Similarly to the worst realists, Greene can have a problem of mood. The novel is gloomy, full of suffering and people struggling just to get by. He paints them with empathy and a bit of humanity, but he can’t get over the distance. In general realists have a hard time doing it. I still don’t understand completely what is it that allowed Carver to make you feel right next to his characters, but Greene can’t captures that. Perhaps it’s because Carver had his weird moments. Most of the variety in tone comes from drowning you in dialogues unlike this novel.

At least if Greene sticks to a single tone, he’s successful at expressing it. The story format helps it. Following a nameless protagonist defined by his role already gives an air of poetry and detachment from the physical world. His poetic yet sparse writing, a more flowery Carver helps with this. Even the landscape in the novel is sparse, with most villages containing little more than a few huts and the big city is defined mainly by having a ship there. His prose isn’t particularly unique. In fact, it follows the ordinary techniques of getting out and in of character’s heads. Thankfully he has enough insight and empathy to these characters, enough focus on making the writing beautiful but clear that it doesn’t harm. He already has a structure to tie him down anyway

Stuck between poetic realism and hard realism, Greene doesn’t reach the best of these but he’s good enough. If this meant to be an expression of Catholic values, it’s convincing. These values appear in overall existence, in day to day lives. God’s name appears a lot, but we see these values in actions, in people sinning, feeling guilty, trying to forgive or refusing to have sympathy for the sinner. It achieves what the best literature should aim for – an expression that leads to greater understanding of human experience and the weird forces in our lives.

3.5 whiskey bottles out of 5